Servers at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, home of Cori (the 6th fastest supercomputer in the world)

The last five years has seen a huge proliferation of internet-connected devices, many of which are produced by tiny but fast-growing startups. In general, startups are at a disadvantage compared to incumbent competitors: they do not have as much cash to invest in development, they have a harder time attracting talent, they are not as well known, and they do not have the same sales relationships that established companies do.

But they do have one advantage: being fast growing can help you juice your metrics. In this post I’ll show that if an IOT startup is growing fast enough, its products will appear to have much better availability than they actually do.

Consider a company selling a server that is availabile 99% of the time. In other words, in a given year of 365 days it is only down for \(0.01 \times 365 = 3.65\) days. (Note that this is actually terrible performance in the enterprise computing world—imagine your whole company having to go without access to its Outlook server for nearly 4 days a year!).

Suppose that the sales for that particular server are growing 50% month over month. Typically, servers aren’t fully up and running the day after they are sold — it takes time to provision them, install the right apps, and put in place the appropriate network and security controls. For the purposes of this argument, let’s assume that for nearly the first month after the device has been sold, it is probably booted up on a rack somewhere but not really running anything (e.g., for our device, we haven’t yet configured Outlook on it or linked it to any storage). This is great for the startup since it gets to count this initial month as time when the device is fully available even though there’s basically zero chance the the device has any issues/downtime during this period.

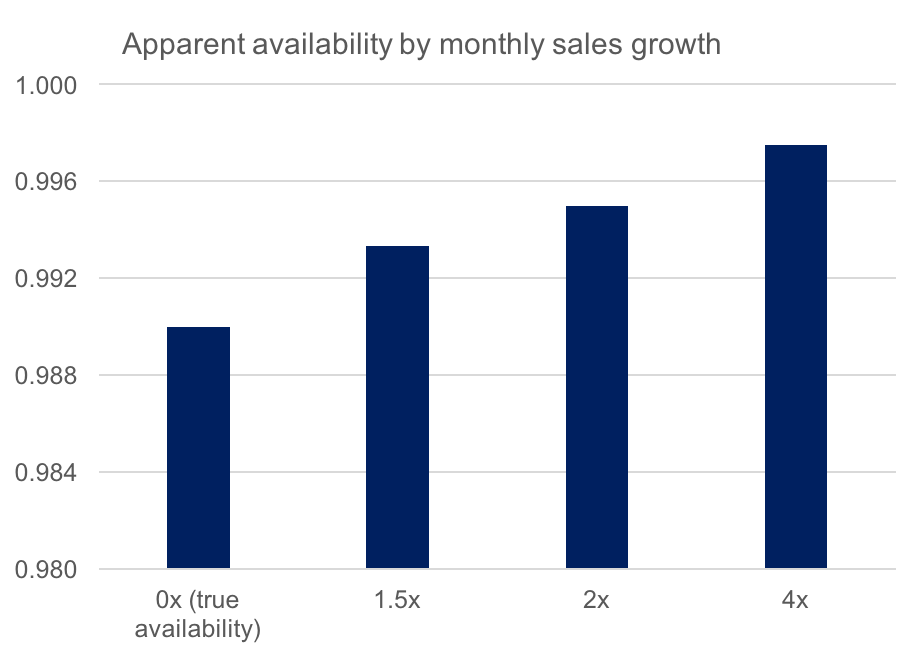

This effect would be marginal for mature companies but it is hugely impactful on the aggregate reliability numbers for small and rapidly growing companies. The chart below shows how this effect plays out over an 8 month period under three different growth rate assumptions (1.5x, 2x, and 4x month-over-month).

Each bar represents the perceived availability for a given monthly growth rate (0x, 1.5x, 2x, and 4x). The true availability for that device is 99%, but the perceived availability is higher than that due to the fact that new devices are not truly being used.

For a company with 4x month-on-month growth (I know, that is extremely high, but bear with me), the actually availability looks very close to 99.9%. By contrast, if there were no growth—and no newly bought devices were sitting on a rack accumulating availability time immediately after purchase without actually running anything—the aggregate availability would look closer to 99%. This 99% number is the “true availability,” what we generally would see from an equivalent incumbent.

Now you might stare at this chart and think “all of these numbers are so high; why does it matter?” But this difference is a full order of magnitude: the company with devices that are actually down almost 4 days a year (99% available) actually looks like its devices are almost 99.9% available (down for fewer than 9 hours per year). For many buyers, this difference can influence the ultimate purchasing decision on a sale of tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of IT equipment. Additionally, it can have knock-on effects (i.e., if I’m hosting an app, the availability guantees I offer to my customers are constrained by the availabilty of the services and equipment I’m using in my data center).

Now, this isn’t an argument not to buy from startup IoT companies. For one, many products boast super-high availability numbers that are much larger than a typical enterprise buyer would ever need (99.999% or even 99.9999% available). And most companies are only in this phase for a short period of time–it would be quite surprising if any startup grew by 4x month over month for an extended period of time (by definition this company would cease being a startup very quickly)! This is just a cautionary warning when buying the next big thing: on at least one dimension, its specs probably don’t reflect reality.