Growing up, The Simpsons was my favorite television show. Friends was a close second and the radically age-inappropriate Maury reruns my sister and I watched when we got home from school comprised a distant third. There is a delightful compact book out there called The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family, which provides more detail than anyone would want on every episode from seasons 1-8. (NB: Ask any Simpsons true believer and s/he will confirm that these episodes were by far the finest of the series.) I somehow persuaded my parents to buy this book for me when I was 10 and subsequently read it from cover to cover, in spite of the fact that all of the information contained in it could be gleaned from owning every DVD and watching every episode multiple times—which I of course did, too.

Fast forward 15 years: I discovered this spring that a kind soul uploaded a massive data dump of 600 Simpsons episodes (episode names, characters, and every damn line from all 600 scripts) to Kaggle. Needless to say, I got pretty excited.

If you’re an avid reader of this blog, you might be aware that I have been on a bit of an NLP (natural language processing) streak recently. A couple of fun facts I found after playing around with the data in a Jupyter Python notebook:

- Across 600 episodes from 1989 to the present, there were 158K lines, for an average of 280 lines per episode

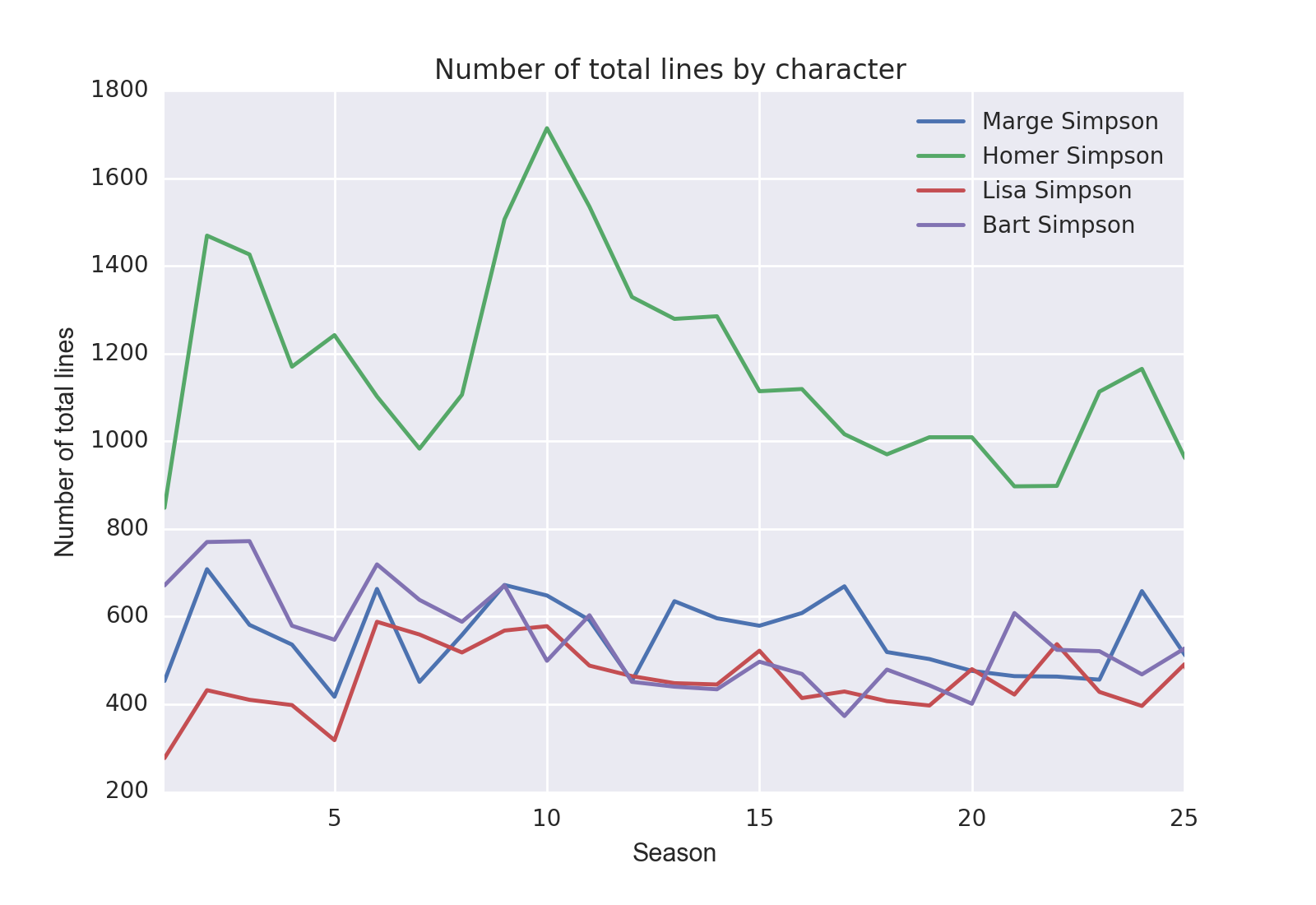

- The character with the most lines by nearly a factor of two was Homer. Marge, Lisa, and Bart trade off on second place depending on the season:

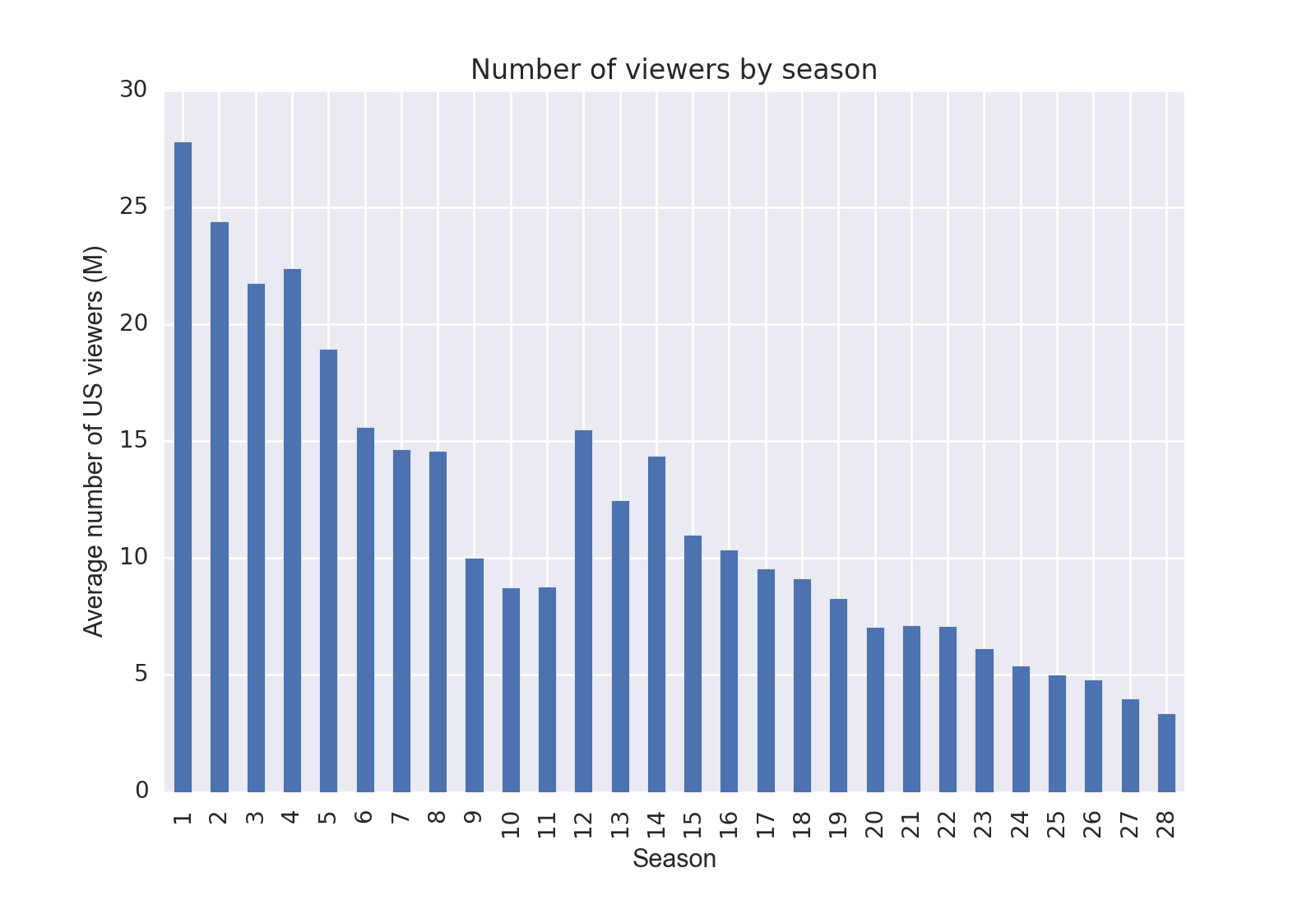

- The show’s viewership declined pretty rapidly as the seasons went on 😞:

- Trying to predict an episode’s IMDB score based on how much each character speaks in that episode does not work. I was surprised by this result because, honestly, who actually likes Krusty the Clown?

Predicting whether lines were Lisa’s or Bart’s (code and replication data here)

One thing I wondered was whether you could predict who spoke a line based on the contents of the line. Certain signals would be dead giveaways, like Homer’s “D’oh!” or Bart’s “Ay caramba.” Most lines without these indicators would be more challenging, though, and would probably be difficult to classify even for Simpsons aficionados like myself.

I was able to build a pretty simple classifier that predicted whether a line was Bart or Lisa’s based on the line’s text content. The essence of this classifier was training a simple regression model based on the frequency of every single word, bigram (phrase of two words), and trigram (phrase of three words) contained in all 24K Bart/Lisa lines. Here’s what came out:

Model results: Comparison of guessing, guessing "Bart" for every line (since Bart has slightly more lines than Lisa), simple linear regression model, and regression model using only lines with 10+ words

Unsurprisingly, limiting ourselves to longer lines makes the task substantially easier (e.g., there are lines that are just single words like “Oh” and “Springfield”—as you can imagine, it can be pretty difficult to guess the speaker based on one word alone). We’re pushing the 70% mark, though, and I’m not sure that I, armed with my hundreds of hours of Simpsons consumption, could do significantly better.

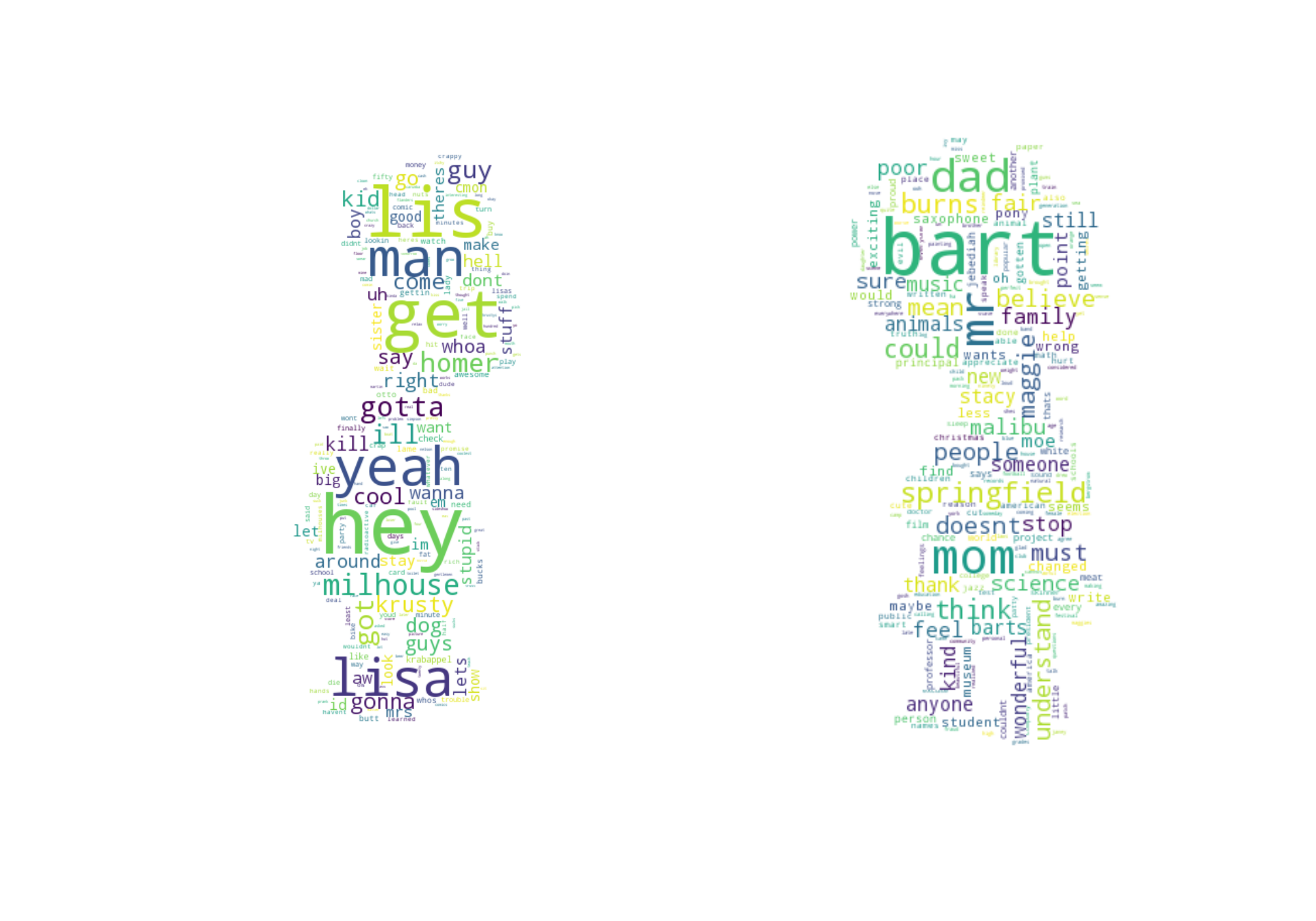

Word clouds

Finally, I discovered a nifty little Python library aptly called Wordcloud. I found that if you run the Bart/Lisa classifier using only unigram (single word) features, you can use the most positive and negative regression coefficients to figure out which words skew most towards Bart vs. Lisa. In other words, our unigram model tells us which words are “Bart words” and which words are “Lisa words.” Armed with that data and my Wordcloud library, I created this little visualization, which was not only pretty but also confirmed that the model was finding words that made sense:

I found it to be rather cute that some of Bart and Lisa’s most predictive words were each others’ names. It makes sense though: they are constantly saying each others’ names in conversation, especially touching scenes like this one.